Naming a place is the birth of knowledge

Naming a place is an ancient idea found in many philosophical traditions. Perhaps in the pre-Socratic Greek philosophy, it was first encountered by Heraclitus, who believed that a name bore an essential relation to an object, and was thereby capable of revealing a truth about it which might not be otherwise known. — Heraclitus: The Cosmic Fragments

In the cold early morning hours of February, as I made my way on the white sand footpath behind Cabana to join a friend for coffee at “The Perch” (the locals’ nickname for the Seaside Pavilion), I noticed a familiar figure in the morning shadows of scrub oak. I would have been alarmed had it not been Jim Foley, the Point Washington-based carpenter, holding a measuring tape and peering through his thick horn-rimmed glasses at the spatial distance between two points. “Morning ladies … measuring to make way for the new boardwalk,” the craftsman broke through our chatter, not waiting for a response before returning to his task.

“Making way for a new boardwalk?” My friend and I looked at each other quizzically as a playful goldendoodle bounded gleefully in our direction. It was Gracie, the town founder Robert Davis’ second dog, out for a morning stroll with her master. She raced along the sandy alleyway to greet us before returning to Davis as he met up with Foley.

While she waited for her owner, Gracie filled her time inspecting plants and assessing her surroundings as she sniffed out significant messages before leaving her own. Once the pathway has been sufficiently marked as her territory, Gracie relaxed on her little lane and wagged her tail in direction of the gulf, all the while monitoring the movements of Foley and her caregiver.

Foley was the third official employee of Seaside, back in 1983. Local legend has it that an architect tipped off Foley to getting work in Seaside from its founder. Foley recalled, “He said that Robert Davis was looking for someone to do nice trim work because nobody was cutting hip roofs any more after the war, they were just ordering trusses out of boxes.” So, one day when Davis was in town, the architect introduced the developer to the carpenter. “He told Robert, ‘I’ve got a carpenter out in the woods doing good work.’ … Robert walked up to my house (at the time, a Volkswagen Bus) and started talking to me about philosophy and building a town. I thought he was Don Quixote, but with his architect sidekick Teofilo Victoria in place of Sancho. For one thing, you could buy a cottage in Point Washington for $3,000 back then. Look around,” he said, sweeping his arms to embrace the surroundings, “Robert ‘Quixote’ did it!”

Foley did it too. The craftsman has contributed his fine handiwork to many Seaside buildings, most still in place now 30 years later — and no doubt Gracie has inspected them all.

On the south side of 30A, spanning from the Coleman Pavilion to the edge of Bud & Alley’s Waterfront Restaurant, Gracie’s Lane would be completed two months after that brisk winter morning, right on schedule, in April. “People are complimenting me, but I can’t take credit other than to have embraced (Dhiru) Thadani’s beautiful interpretation of Robert’s dream of a boardwalk along the gulf in Seaside,” said Dave Rauschkolb, owner of Bud & Alley’s. “We are so thrilled.”

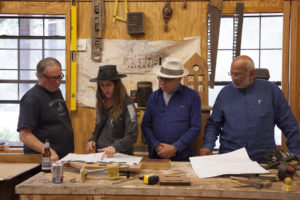

Town founder Robert Davis and craftsman Jim Foley discuss plans for the new boardwalk. Meanwhile, Gracie seems content to be recognized alongside her owner’s dachshund named Bud and the feline Alley, for whom the restaurant is named. With the anticipated expansion of Bud & Alley’s toward 30A, the present east–west alleyway will cease to exist. The new circulation route between east and west will be along the new boardwalk connecting the Coleman Pavilion to The Perch. The seating area of Bud & Alley’s along the boardwalk will be reconfigured to one level, making it more efficient for dining and private party events.

Gracie’s Lane features a 150-foot bar made of warm African Sapelle wood and will accommodate 50 bar stools that overlook the Gulf of Mexico, creating yet another sociable place in Seaside. The wooden countertop sections are joined with inlaid brass butterfly connectors made by Manish Waghdhare, the Indian artisan who has contributed much to Seaside.Atop the counter are wooden house-form lanterns, each fronted by a removable ice bucket embedded into the countertop to chill beverages on hot summer days. Seaside vendors are prepared to sell buckets of beer and wine for the new gulf-viewing counter; and of course, there will be a water bowl for Gracie and her friends.

Under the counter, Manish cast playful brass hooks for conveniently accommodating handbags, towels and coats. Electrical outlets and USB plugs are incorporated for those who need a quick charge for their communication devices. Eight-foot long strip lights are enclosed into the deck flooring to insure that the sea turtles are safe from direct artificial lights, while illuminating the path.

The boardwalk’s designer, Thadani, an architect and urbanist, grew up in Bombay and has been involved with Seaside for 38 years. Growing up in India, Thadani was surrounded by pattern on every surface. “I am intuitively attracted to pattern, yet my early modernist training instilled in me an appreciation for unadorned surfaces. I try to balance those two sensibilities.”

It is early May now. Spring break season has come and gone. There is again — a silence. It is just before twilight on the eve of one of those glorious sunsets, when shades of pink and blue softly diffuse into night as the sun falls below the horizon. I’m treading along the forgotten sandy footpath with my pack of girlfriends as our bare feet alight upon the new boardwalk. A warm breeze blows as we wish to one of us a happy birthday, and wait for the sunset bell to toll from the rooftop at Bud & Alley’s before raising a toast to celebrate another year passing for our beloved friend. Alongside us are other locals and vacationers who have joined in our reverie — even Gracie made an appearance, as if on cue.

Here on Gracie’s Lane, we are all in the company of indigenous scrub oak, so carefully protected by Thadani’s design, Foley’s craftsmanship, and Davis’ vision. We, too, are among those indigenous species that are sheltered from the harsh realities of suburban living we left behind.

For this sunset, we’ve gathered here, in the spot where Foley stood with his measuring tape. Here, where the distance between two points has now been joined together. The moment reveals a simple pleasure that felt uniquely unavailable in the “old days” of early February. Here, in this once hidden refuge where we gather to appreciate each other and one more valuable stage of life — in our hometown.

Rauschkolb reflects on those early days at Bud & Alley’s. “It is such a treasured dining tradition for 32 years to eat under the stars in the herb garden dining area and gazebo now enhanced by this beautiful boardwalk,” he says. “So many years ago, I’ll never forget how I felt watching the first diners enjoy a great meal in the open-air herb garden. At that time, when you looked west there was no gazebo, no homes, no WaterColor, nothing except the seemingly endless green expanse of scrub and the deep blue sky.”