Stefan Daiberl, born in Augsburg, Germany, in 1970, moved to the United States in 1997 to pursue a masters degree in business administration (MBA) from Babson College, which he received in 1999. In 2002, he left Interbrand, a New York consulting firm focused on marketing consulting and opened Craft, an interior design firm located on Scenic Highway 30A. In 2007, Daiberl abandoned his business pursuits in order to focus on the arts.

His first exhibition, The Ecdysis, considers the vulnerability of the creature during and right after ecdysis, which is the molting or shedding of the skin in arthropods. Stefan Daiberl’s Ecdysis deals with issues of personal growth, psychological change, crisis and subsequent evolution.

Hunter: Your metaphors of expression involve themes of nature and found objects extracted from the environment and you use them as explorations into human psychological and social phenomena. Why are you drawn to these themes and how do they relate to the principles of psychometry, the theory that all objects give off emanation?

Daiberl: You touch what you are made of, you know? I think that an artist needs to have the capability to sense the emanation that things give off. I think it’s very important to see an object not just for its surface but for what it really is, what it contains and what other people see in it and what it is loaded with in terms of meaning and history. The past is entombed in the present.

Hunter: Some artists choose literature, canvas or film to express, but you have chosen objects. For me, that doubles the interest in your work because you do two very huge things. You are communicating something very important and then you are using natural objects that have those powers.

Daiberl: It is a predisposition that I have to connect experiences to objects and I record sensations in the context of objects that are around me. Past sensory experiences, visual, tactile, olfactory or otherwise now help me materialize physical works. I often unconsciously record moments of life that are important using objects that surround me as the recording device.

Hunter: Why do you have an interest in this?

Daiberl: It lies in my personality somewhat, but it is also tied to where I grew up. It’s tied to my family background of very earthy and hard-working people in Bavaria, Germany. Bavaria is mountainous and rugged and suffers from a physically very demanding climate; it’s like Andy Goldsworthy living and working in Scotland. You see these things as you wander through a forest in a certain wood that you might have wandered through as a teenager. And you may realize that what you are is somehow related to what is around you. An oak tree, a smell, the way the light cascades through the forest.

Hunter: That’s interesting because that is almost a language. Those objects were almost forming a language.

Daiberl: For me they are. If you read Perfume, the novel by Patrick Suskind, for example, and the insanity that is related to a person having an incredibly keen sense of smell. Then relating the experiences in relationships and interpreting that through the creation of a scent. It is almost like that for me. Some people remember a lover by a song, where I will remember the time spent in an Italian landscape by a tree, or by the color of a plant or by the smell of wild garlic that grows there. It’s the environment, it’s me and it’s also my family. My father showed me these things not knowing that they would impress me that way.

Hunter: Are you just beginning to reconnect to these natural objects that your father introduced you to?

Daiberl: Yes I am. And, I am trusting my gut feeling more now when I see something. This is the strange and remote tickle that I get from looking at something that’s out there. I never had the sensibility to actually go and investigate that. Like stopping your truck on the side of the road and walking into a forest to actually look at that plant and take a piece of it. I would not have done that five years ago.

Hunter: That is very instinctual. That is your core language. You are reconnecting back to your family.

Daiberl: Yes, to my family and to my origins as a human. This development only happened because a crisis made me need to go through it. When you are unraveling as a person, for me the most calming and soothing thing to do was to go out into a forest. Like right now, I just had this argument on the telephone. It makes me want to paddle away on the gulf. It makes me want to just look at a plant. Or go nail things into a board because that brings me back. The material contact brings me back, it is re-grounding me.

Hunter: Re-grounding you into your own heritage. You are going back and pulling forward these objects that once grounded you in your life. You are re-communicating these emotions through art rather than wasting them on trivialities. You mentioned exploring that concept further in sacred places.

Daiberl: The interest in exploring it further came from a sensation of up rootedness and homesickness that I perceive from being out of my culture in my life or out of my home. I tried to understand what it really is that I miss about my home. What it really is that is that strong connection? What is the basis of that? Rather than saying that it is people or family, I keep saying that it is really places. And it is the feelings in places that connect me because the first thing I do when I go back home is that I go back to certain places.

Hunter: And through that experience of going to a place, you are reconnecting to emotional experiences with family or to the objects within those spaces?

Daiberl: I am connecting to my own history as a human because my history as a human is the last chain in a sequence of events of people having the same experience. For thousands of years in my town, people have wandered the streets like me. I am just the one who does it right now. I have wandered the streets and I have become part of that environment because other people have been there before. So in the artistic approach what I am trying to do is extract the essence of what these places do for me. And that is when I begin thinking of the concept of psychometry. Can you really take it so far as to taking an object and its powers in that way and making something of it? How do you do that? How do you make that sensation transportable?

Hunter: And allow someone else that experience when they encounter your art.

Daiberl: Yes, exactly.

Hunter: I would say that you have successfully done that.

Daiberl: I don’t know but my first thought, when I felt alone and lost and full of turmoil was to make a first aid kit. Something that hangs on the wall and has a red-cross on it and put relics in there. Almost like a shrine of relics that you would find in a Catholic church. The bones of a bishop and the bones of saints, and in the same way I wanted to make something that contained a group of objects or sounds or smells or things that I can go to during these times of being lost. You open it up and there will be a piece of a wall in there, and there will be a recording of a sound in a specific church and there will be an image of something and there will be a letter that someone has given me. There might be a pebble from the beach that I used to go to. Things like that and that conglomeration would make me want to go there and open it up, look at it, walk away from it and feel like I was where I was supposed to be for a moment.

Hunter: And you are investigating this in your own life.

Daiberl: I have listened to people on planes, for example, where I hear them say things like, oh yes, I’m Irish or I’m German, but they are fourth generation, yet they still say that they are Irish or Scottish or French. And then you ask “Have you been there?” and they say “No, but my great grandmother came from there”. But I see it, you know, I see it. I see that everybody carries that definition of themselves in them, but nobody really investigates or enjoys that link or seeks it or tries to really investigate why they are the way they are, and why they feel the way they feel.

Hunter: Are there other artists who are exploring this through their art in the way that you are?

Daiberl: If you listen to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, for example, in that classical piece of music you will find the love and the passion that he had for a landscape in Italy in the summer, in the winter in the spring, and in the fall – in the sound of that music. You hear it in the sound of that music. I think that is probably the closest to what I see.

Hunter: You are exploring the metaphysical connection to objects and how they can heal you, which may be a more powerful healing agent than the object itself.

Daiberl: Yes, I am, and they can. There is a way to transport a sound or transport a scent, make an imprint and cast things. I have been thinking about making a book about traces of humanity. I was in a church in Italy recently. There was a brass door handle that was totally polished, shiny bright and polished. It was polished because it has been there for hundreds of years. There was an indentation about two inches deep in solid wood just from the brass banging against it. Can you imagine how many times that thing banged against that door in order to make a hole in that wood? Probably a million times.

Hunter: A million times containing the motion of each individual that was knocking and all of their feelings, which would be their emotion, their e-motion. That is interesting. It makes me wonder if humans are capable of stepping into and out of their own emotions, and into every moment of motion through time.

Daiberl: What matters to me is that person that went to the church for a reason. The fact that all these people touched this handle and entered the church for a reason of prayer; for a reason of grief; for a reason of happiness.

Hunter: What is The Ecdysis to you?

Daiberl: That’s a big one. The Ecdysis, the whole concept, sounds so premeditated and planned but is more like an unexpected end result of individual works that are in it, which were a result of me dealing with very individual situations that I found myself in at the time that I made each one of the pieces. Each one of these pieces followed a very strong personal impulse at the time that I made it. It was more like a therapeutic exercise to make these things in order to leave the skeleton behind. Each one of these pieces forms the whole unit, which was a surprise to me. Every piece represents a shedding.

Hunter: Every piece in and of itself represents a shedding of one experience after another. Will more pieces come forward over the next months or even over your life time?

Daiberl: Yes, I think growth occurs in spurts. You go through some development and there might be a crisis that spawns and you grow and there might be a period of stability and you are forming and building. Just like the animal does it. You go through a period where you will shed something and then go on to the next thing. I am in a different place now where I am not shedding as much. I am finding myself again and I think there will be more stability in the work I make. I will select something and try to perfect it. Then Ecdysis was born out of an absolute need- a critical need- for me to deal with my own life situation. Finding these objects and intricate mechanisms that I used to make these pieces has really grounded me.

Hunter: The shedding is a very human experience – we all have it. We all go through this shell shedding and have this experience which evokes the deepest pain and fright. The pain of growth. This is why I have felt so moved and impassioned over what you have created. I have observed people viewing your work and watched for their moment of realization. The moment when they feel their own pain through viewing your work. In that fearful moment, you gracefully show them that this is a human experience, nothing out of the ordinary.

Daiberl: Yes, and I didn’t really plan to do that.

Hunter: The term monomyth refers to a basic pattern found in many narratives from around the world. In the monomyth, the hero begins in the ordinary world, where he receives a call to enter an unknown world of strange powers to face a series of tasks and trials. Through its inception and ultimate creation, were you aware of The Ecdysis as your own monomythic experience and of its potential impacts on the world of art?

Daiberl: That is interesting. It is interesting in the way that people meet challenges, like the hero in the monomythic stories and how the hero responds to these challenges by succeeding and learning something . I didn’t know that I was sent out to meet challenges and work through them and come out stronger in the end. The heroes in the monomyth know that they are sent out to the sirens on the cliff and that they have to face them and be strong and share their wisdom with the world, if they survive. It was not like this for me. I found myself in a painful personal situation without having chosen to embark upon this journey. The journey came upon me I didn’t make that choice at all; I was just trying to survive.

Hunter: What about the fright of that experience relative to your mention of Dante’s Inferno. Alighieri vividly describes the horror and sickness of that experience. My mind goes to the circuit board piece where I see the drill, the hooks, needles and even a tooth. Those are objects of fright which are indicative of the hero’s journey that is riddled with tremendous pain.

Daiberl: I tried to find the pieces that contained the feelings during the experience that I went through in the moment. It is related to the whole concept of psychometry and the sensitivity.

Hunter: And the wedding band and the tooth and the needle from the surgery, it almost looks like a wicked doctor’s torture chest.

Daiberl: Yes. I decided to keep them and this piece was shaped in the size of my chest. I measured my shoulder width. It was called Psychometric Body Armor at first. I felt just like an Indian, a person in a tribe, who would wear ceremonial objects around his or her neck for protection, like the tooth of a tiger. These things on there are to shield me.

Hunter: The ritual experience is absent in our culture today. You are expressing rites of passage.

Daiberl: Ritual is important. All of my pieces are ritualistic in the way that their assembly usually includes large numbers of small objects, and working in this way is a very trance-like ritualistic experience. These pieces here, for example, are hammered into metal. It is a very labor-intensive, long and drawn out process. The wedding band is locked in there by steel wires guided through 200 very small holes in a metal plate.

Hunter: Tell me about the wedding band. This communicates a lot about our culture and marriage.

Daiberl: The wedding band. I had that relic, and there were a couple of options. One was cutting it into little pieces and mounting it in chunks, but I was reluctant to do that because I wasn’t sure if I wanted to throw it away – you know the relationship, the whole thing. There was also a sense of danger. It’s locked up. It is really in there for good. But it is also a little bit protected. I was not giving it away. But it’s gone. I know it’s gone. For me it was really about the torturous process of dealing with this object by spending half a day drilling holes around it and tying it up. It was very cleansing. . The initial human reaction is to put it in a jar and just forget about it.

Hunter: And that experience that you had in creating that piece – fast forward to the moment that I and others heal through feeling that emotion connecting it to our own experience. That is the emotion that evokes the pricelessness of art, and this is the bridge. The object emanates emotion and connects people to this very pure moment. And that object contains emotion. This is just now hitting me. The art in and of itself is an object but the psychometry of that object is what connects people to it. This is what you understand, and I am just now coming to that understanding in this moment. Wow.

Daiberl: Things have the potential to do that. They have layers of meaning, Human emotion is stored in objects and objects offer that connection back to the core of being human.

Daiberl: We are all rooted in the same things. The world is a closed system – nothing leaves it and nothing new comes to it. We are all made from the same material. We are all somehow equal. There are objects and situations and moments universally applicable to everybody.

Hunter: Somehow there was a disconnect that disallowed people from that pure experience and the reconnect is the priceless aspect of art which is psychometry. It is linking back to the movement, and that movement is what we call emotion.

Daiberl: Yes, and we are surprised by it.

Hunter: Yes. You can speak in the business language, you can speak on a soul level, You have the resources to express. You are in a physical place that disallows a lot of human social experience. That is a unique equation.

Daiberl: I am able to isolate myself from the things that kill, abstract work that kills your sensitivity. I don’t have to deal with a relationship that bogs me down and makes me dull to the world. I can lock myself up in my little world here and explore that.

Hunter: As a child you were creating a language for yourself, through your experiences in Germany. You began to connect objects to language.

Daiberl: Very important was that I was enabled by family to be in places that allowed me that experience, like the mountains and the rivers and the oceans, the scents and herbs and flowers. Unconsciously, I was exposed to that at the most important time in my life and I carried it with me.

Hunter: Part of what you may be experiencing was the enjoyment of a childhood where you were unencumbered, a connectedness of the two worlds. You were living in a very connected world that was broken apart.

Daiberl: Yes, it had to break apart and I had to put it back together. I have moments when I can shield myself. It is very painful for me to be ripped out of that connection. All I want is to be in the moment of the realization of how these things materialize.

Hunter: What you probably did not recognize as a child is that you were uniquely connected to your environment.

Daiberl: I spent a lot of time alone as a kid. The way people connect is by using everyday situations and things as media. I just can’t share those experiences. I just cannot participate. Those are things I have to deal with as part of society. I sit at a party. I just don’t have anything to share which leads me to wandering around somewhere, other than being with people.

Hunter: You did, at a very young age, have a powerful connection and lived in that understanding that everything is connected.

Daiberl: The older I get and the more I talk to people who are getting older, the more I realize that age is important. Older people are reconnecting. There is an expectation of death. The touch of death and the expectation of death and ending. Somehow approaching the end forms a new beginning. That absolutely finite quality of human life is one realization to me as a person and as an artist that was very important. The realization that you are mortal connects you to those who have been here before. And, as a next step, makes me sensitive to the objects that have been touched by those who were here before.

Hunter: It makes perfect sense because this is what you profoundly understand and you want others to live in that understanding. The longing is for them to know what you know and share that experience.

Daiberl: I am not consciously wanting anybody to get anything from my work but I do want to reach a point where I am understood and I can talk to people and get something back that actually feeds me and nourishes me, where I can have a continuous dialogue. I rarely get that. Sometimes I get comfortable silence and that comfortable silence is usually enabled by nature.

Hunter: What about your education?

Daiberl: I went to some very demanding schools in Germany. It was very tough and a solid education. I went to university in Germany when I was 20. I worked for a metal smith for a year. And then I had this idea that real men have real jobs. My dad was a very successful business man. I was not intuitive enough with my family and cultural background to follow the pursuit of a creative career. So I signed up for business school again. In my early twenties I was ok. But when I turned older and got my masters, I became really good at school. I was one of the best students in the school and it was because I found a way to lock myself up in a room and copy books in handwriting. I would take a textbook of statistics and write the whole thing down and then I would understand it. I had two professors who took an interest in me. One of them suggested I go to the United States and further my academic training, so I enrolled at Babson College and got my MBA there. I was very good at it. I think that a lot of my academic performance came from the aesthetics of the work itself, arranging things, the ability to making order out of chaos is really what made me good at school. Presenting and dealing with complex data, that’s really what I did.

Hunter: And you have incorporated that education and experience into the creation of art.

Daiberl: In business school, I was sorting out multiple units of something to reach a meaningful conclusion. That is also what I did in consulting in New York. I was the presenter. I was the speaker. My work was based on organizing complex data. I liked what I did for the aesthetic reward of having organized some complex data into clear order. In management consulting there is really no right or wrong, true or untrue. I was in control of everything from the data collection to the presentation of the product. The causalities between a presented result or recommendation and its effects were very murky. Nobody could really say that what I did was wrong. This whole experience really made me want to work in a world of tangible products with authentic character and integrity.

Hunter: What about the transition to art?

Daiberl: My design shop Craft was the transition. I felt that I needed to have a business because that is how I thought you make a living. I was looking for a business that had equal amounts of creative outlet and a business core. I could tell my parents that I was working and that made me feel good. The business lost a lot of money and it didn’t really work. I got great satisfaction out of going to furniture shows in Milan and Paris or wherever and seeing things that were very beautiful. I was definitely admiring things that were well crafted. I drooled over objects that were authentic and made with integrity and it wasn’t at all about the interior design aspects of the business. I loved seeing the people in factories in Italy or Austria that cut leather from whole hides and hand-stitched it into covers for furniture.

Hunter: Can you describe the transition of exiting out of this business and into the first piece in Ecdysis.

Daiberl: I think this whole transition from being a retailer and a designer was sparked by intense personal crisis. I just kept feeling that I wanted to go into the woods and collect things. Deal with me as a human machine. I needed to make something in order to make myself live. I can’t really explain that sensation and how it worked, but it was a survival mechanism to start making these fragments of myself in order to preserve them so that I can still be around. I am still here because I have these relics of myself. I have tried to assemble my world at the same time that it was falling apart.

Hunter: Your worlds were meeting. I keep going back to psychometry here because I am fascinated by it and you introduced me to it. There was a quest. You mentioned the doorknocker. There is a quest for the emotion of that moment; it was almost like to worlds converged. When your art began, those two worlds came back together and psychometry left your life and the emotive aspect possibly disappeared. Does that make sense? Perhaps you were tapping into the absence of pain. I don’t know how to describe it but the emotion behind the creation of art converged on the moment and helped eliminate the pain which carried those moments to other people.

Daiberl: When I created the “The Comforting Insignificance of Your Lifetime” that illustrates what you just said.

Hunter: How do you are articulate that? How does one put that in words? It is as if you caught up with time. Psychometry is time.

Daiberl: Yes it is time. It is the power of the passage of time. Time is stored in things. I think there has to be more. That is why I am looking in places where emotion is involved.

Hunter: What of the human trace?

Daiberl: It takes you back to the elimination of pain. “The Comforting Insignificance of Your Lifetime” is what calmed me. The age of the wood, the age of the metal, touching the things that were here before me and realizing that these things will be here after me. I realized that there are things out there that are greater than your own misery, and there are objects out there that when dealt with make what you go through seem less significant. These materials are what attract me. It is the old wood – it is the things that a million people touched.

Hunter: And that may be the significance of your interest in psychometry. When someone views a piece of your work, there is the psychometric experience. Art is a healing agent, and that is how art heals.

Daiberl: This was not premeditated. It was just for me, but if it does it for other people that is great.

Hunter: Your explorations without your knowing are tapping into a greater understanding of human emotion. This is kind of a big deal!

Hunter: How do you value art in your life now, as an artist and why are you setting aside a degreed life and a successful business career to become an artist?

Daiberl: I think it was a result of an immediate need to survive for me, and I was looking for a mechanism that would keep me here and I very intuitively, like a child, played and materialized these things that made me and shaped who I am. It is the fascination of having a sensation of “this is who I am” and “this is what I just realized about something” and being able to make it into a thing – and then you step away from it and you have something hanging on the wall. And in that moment you realize that this is the translation of all of the things that went into me as a person. It feels good. I feel proud.

Hunter: I would venture to say that considering yourself as an artist was not even in your thinking.

Daiberl: No, it wasn’t, and I still feel embarrassed about it. I don’t feel like an entertainer.

Hunter: But I would argue that you are a teacher. A true artist is teaching about a piece of knowledge or understanding that is not yet understood. What makes you unique is that you are teaching through found objects, which form a language.

Daiberl: There are certain objects that store things. Look at Duchamp’s Fountain Urinal! They store meaning and emotion that is universally applicable to humans. The medium with which these contents are communicated are aesthetics and beauty, and I think that the content that objects communicate is the aesthetics of beauty.

Hunter: Is the shell-shedding experience worth it? The piece called Pandora’s Box really tells that story: the risk of opening the box and the pain relative to joyfulness. Have there been moments of happiness?

Daiberl: I made that piece in a dark moment; it was really a satire of hope. It’s Friedrich Nietzsche’s view of the concept of hope that’s on there. Greek mythology says that all of the evils came out of the box except for hope. And hope was in there but Pandora closed the box again. Now you can think or say “why is hope still in there?” Is it something to look forward to? Is it in the box because it is good, or bad? The interpretation of Nietzsche was that Hope is the worst. People will always have hope and therefore put up with all the other little evils that came out of the box and keep tormenting them.. I dealt with the concept of hope at a moment when I did not have any. It was a very immediate translation of the need for hope in my life. I felt as if there was no hope for my family, no hope for me; that is why I dealt with hope by hammering Nietzsche’s letters into a piece of metal. It was a very immediate and desperate attempt at trying to find hope by quoting someone who is denying its existence.

Hunter: What are your feelings of hope now, after this experience?

Daiberl: For me, in my own evolutionary process, I think there is hope and the hope is the result of a redefinition of my own expectations as a human. It’s a basic growing up experience. When you are young. you always want to get to ten on the scale of happiness. And on your search for the perfect ten, you will eventually encounter some very painful ones. In that hopeless moment you develop a new frame of reference and a new set of expectations that enable the development of hope.

Hunter: And I wonder if the hope is about the return to this experience, that pure place where art comes from, which may place of pure happiness, nirvana. I hope you will show us more examples of that in your work.

Daiberl: I now see glimpses of happiness in many things. I have not worked artistically long enough to have a constant stream of these glimpses . I have to set up a system in my life that allows me to float on that. I am starting to discover my own personality, my skills and inclinations, and that discovery has the potential to give me hope and eliminate pain. My work does that. For me it is now about establishing this whole new life as an artist with all of the sacrifices and commitments associated with that. You need a job. You need money. You need things other than just sitting in your studio.

Hunter: Where do you find yourself relative to your art?

Daiberl: I think that I will never make something that is purposefully contrived to cause a reaction in somebody. I am interested in making things that utilize the potential connection between a human emotion and an object. I am going to keep investigating my own feelings and sensations to find these things that illustrate this linkage and that can bring people back to that human experience. I want to find things and assemble them in a way that is humanly meaningful. I am not going to intentionally teach but I am going to listen to what moves me. I am going to hope that the things that move me will appeal to others as well. I think that my art is going to be not very literal. I don’t like things that are “in your face” about their story. I just recently read something about Jackson Pollock and about how every dripped paint line was intended to represent an understanding of life that he had. The way things are assembled communicates human experience. Something thick can meet something thin, something metallic can meet something that is made of paper. You can pierce something that should not be pierced. I like making vast abstract things that on second sight illustrate something meaningful. That is ultimately what appeals to me, assembling things in a meaningful way. That is where I want to be.

Hunter: I think you have succeeded in doing that and effectively communicating that is a responsibility. I would like to be just as masterful in communicating who you are.

Echoing behind The Ecdysis is the realization that Daiberl has transcended his humanity and re-associated himself with the powers of nature, which are the powers that guide our lives. The purpose of the artist, who is also a teacher is to communicate new understandings through his creative works, returning the jewel of understanding to the world through metaphor.

In Daiberl’s case, as artist and teacher, he offers a great lesson to us all. The example of one who has opted to sacrifice the physical desires and fears to discover what best fosters the flowering of our humanity our contemporary life, and fortunately for us, to that one thing he is dedicating himself.

Photo Captions for Artist Portrait Study: Stefan Daiberl’s Ecdysis

Photo Credits for all images: Michael Granberry

EXHIBIT PHOTOS

“Hope”: Friedrich Nietzsche’s interpretation of the concept of hope hammered into polished stainlesssteel mounted on reclaimed cypress board.

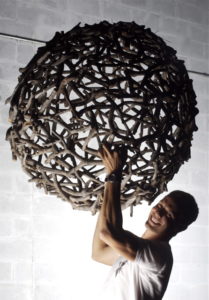

Spheres of various wood in three sizes. These contemporary sculptures illustrate the natural beauty of Florida’s Gulf Coast.

The Ecdysis will be on exhibit again this fall in the Courtyard at Rosemary Beach.

A perfect shape formed out of imperfect material may surprise with a stunning three-dimensional visual quality.

Exuvia: Human spiritual growth may be a result of encounters with very hard places but when growth occurs this way, the shell of the former self will be left behind and we can emerge greter than before.

The Comforting Insignificance of Your Lifetime: Found rusted sheet metal, paint and nails mounted on reclaimed cypress board. This work points at the ephemeral quality of a human lifetime in contrast to the infinity of nature and its contents.

Published in 2008 VIE Magazine Issue